by: RENEE MONTAGNE

When the Taliban were driven from power in 2001, they left behind a broken country and an infamous act of destruction: reducing to rubble two monumental Buddhas that had stood for 1,500 years.

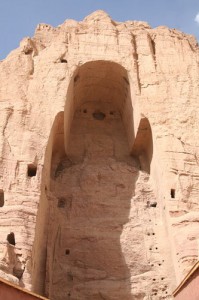

Five years later, it is still a shocking to look across the Bamiyan Valley and see two huge empty spaces where the Buddhas once stood. Nowadays, there is plenty of activity at the foot of the sandstone cliffs where Buddhists monks spent decades carving out the giant statues. The larger of the two statues was 12 stories high and nestled in a space nearly 20 stories high.

Georgios Toubekis, a German architect and professor, has spent the last two years overseeing a team of Afghan workers collecting fragments of the Buddhas. It’s a project of the International Council on Monuments and Sites. A second team, consisting of Italian engineers sent by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) is also at work on the site.

“After the Taliban destruction, there were cracks everywhere, and they’re putting a set of anchors in the cliff to prevent it from collapsing,” Toubekis explains.

A mass of debris sits at the foot of the larger Buddha. Toubekis figures that workers have collected and identified two-thirds of this statue. A storage facility houses fragments, some of which look like big boulders and weigh several tons. Toubekis says he hopes that the pieces will be preserved for posterity.

A Buddhist pilgrim from China who followed the Silk Road through Bamiyan in the year 632 wrote that the Buddhas shone with gold and jewels. At the time, they gazed down through the sunlight on a valley bustling with 10 monasteries and 1,000 monks.

The Taliban weren’t the first to assault the Buddhas.

“Destruction has been taking place since the time of Genghis Khan,” Toubekis says. “He was the first one who shot at the figures, with the intention of demolishing them at least.”

The Emir Abdur Rahman arrived near the turn of the 20th century to conquer a rebellious Bamiyan and then turned his artillery on the Buddhas.

Ultimately, it took modern explosives and the determination of the Taliban to blow the Buddhas to bits.

It’s not at all clear what can be done or even should be done with all the pieces now being inventoried.

Experts say it would cost at least $30 million to reconstruct just one of the Buddhas. Some insist that the catastrophe that befell them is now part of history and these ghosts should remain as they are.

Others argue for using an artful technique now favored by many preservationists: Original fragments are pieced together in a way that makes clear what’s gone.

Habiba Surabi, Bamiyan’s provincial governor, would like to see one Buddha be rebuilt in hopes that it will draw tourists back to the valley.

There are enough precious ruins in Bamiyan that UNESCO has declared the entire valley a world heritage site.

An ancient passageway cut into the cliff behind the Big Buddhas is lined with manmade caves, where the close followers of Buddha would come to worship. As recently as 30 years ago, the cave walls were covered in colorful murals painted over hundreds of years by monks.

Now, 80 percent of the cave paintings are gone — scratched off by the Taliban or carried away by looters. But the monks may have left in Bamiyan one more great treasure yet to be discovered: the so-called Sleeping Buddha, even larger than the ones that have been destroyed. At least one archeologist, born in Afghanistan, has devoted himself to the search, excavating a site since the Taliban fled.

As for Toubekis and his team, they’ve now closed down their operations as the snow seals off Bamiyan to the outside world for the winter. Come spring, they’ll be back to pick through the pieces of the giant Buddhas.