With an electorate that is largely illiterate, the campaign – like its predecessors – was a highly visual affair, with faces of numerous candidates staring down at the people from the heights of billboards. Among the many promises of a better future there was a “Yes We Can” message, looking oddly out of place in Kabul’s dusty environment. Given Obama’s lack of faith in Afghans, the copycat message was unintentionally ironic.

But how does voting work in a place where most people are acutely politically aware but can’t even read their candidates’ names? I have perused the lists to get a sense of what voters hold in their hands when casting their ballots.

Judging by the lists, the vast majority of candidates were independent, having no party affiliation. In a conformist society such as Afghanistan, this display of individualism is rather odd. Cynics would argue that independent candidates are easier to bribe, hence candidates’ reluctance to appear linked to a larger organisation. But it is equally true that political parties are chiefly known for their war atrocities and so, being associated with them reduces candidates’ chances of success. This, too, explains the appeal of independent candidacy.

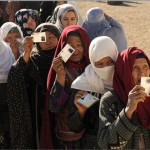

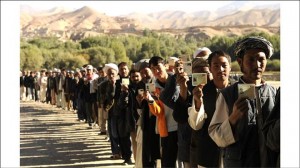

Given the sheer number of candidates, making a choice must have been a daunting task for many voters. With little indication of candidates’ political orientation, voters were left to draw upon visual clues, and titles carried in names. Those unable to read had to rely solely on photographs and symbols – but what sort of politics are voters supposed to associate with images of shovels, envelopes, and aeroplanes? Democracy and illiteracy don’t seem to go smoothly together.

Candidates’ photographs were equally unhelpful. The only candidates that stood out were the attractive ones and those sporting striking beards or interesting headgear. A few stood out because they were smiling. Other than that, the lists were a fair cross-section of largely anonymous-looking, average Afghans. The sheer length of the lists must have been disorientating, perhaps explaining why some electoral officials allegedly felt tempted to interfere and manipulate voters.

Aside from the bewildering lists of nearly identical-seeming candidates, the election bore signs of both positive and negative trends. Positive change chiefly manifested itself in the candidacy of women and members of religious minorities, including Sikhs and Hindus. But even such encouraging trends were often testimony to the courage of candidates rather than reflecting a more open society.

In the words of Partapal Singh, a candidate of the Sikh community, despite having lived in the city for centuries, Sikhs are treated merely as guests in Kabul. Kabul is a city of immigrant returnees and in Partapal Singh’s experience, most of its inhabitants have little idea of Kabul’s history of religious diversity. Like most candidates, Singh found that his campaign posters had been torn. But unlike most candidates, his defaced posters had threatening messages written on them: “You are an infidel. How dare you stand as a candidate?” Yet the fact that Partapal Singh’s supporters were not exclusively Sikh and also included young Muslims shows that democracy is indeed taking root in Afghanistan.

While international media outlets focused on Taliban threats of violence, internal tensions that appeared in the election – unrelated to the Taliban – were largely ignored outside Afghanistan. The most regrettable tension was ethnic distrust chiefly felt in the Hazara community.

As with other traditionally-sidelined groups in Afghanistan, exile and jihad have equipped the community with an acute sense of historical injustice and desire for equality. Given this background, voting arrangements should have been planned very carefully in Hazara-occupied places but, judging by early reports, in some neighborhoods and districts polling stations either closed prematurely or simply were not opened. Voters also complained of a shortage of ballot papers.

The reason for these shortcomings is so far unclear but some Hazaras regard it as a deliberate attempt to exclude their community from the country’s power structure. The fact that because of Taliban threats, large numbers of Pashtuns have also been excluded has failed to persuade some Hazaras otherwise.

Interestingly, similar accusations of deliberate manipulation of democracy have been raised against the Hazara community itself, chiefly in the city of Herat. In the absence of proper investigation, such inter-ethnic disputes are usually left unsolved, allowing resentment to turn into hatred, further damaging the process of democratisation.

Judging by initial reports, the most enthusiastic voters were the traditionally excluded entities, ethnic and religious minorities and women in calmer urban centers of the north and west. But even in these regions, rural voting patterns had all the hallmarks of block voting, and sometimes fraud.

Observers have also noted the conspicuous presence of a new class of wealthy Afghans who owe their wealth to reconstruction and contracts with the US army. Members of this new business class have been observed trying to buy votes, either by paying henchmen to stuff ballot boxes or by entering into deals with community leaders.

It is highly ironic that the same class that is the greatest financial beneficiary of the US mission is also the one that is undermining democracy through corruption and in doing so, damaging the US’s reputation in Afghanistan. But then again, historically Afghan elites have always caused their own downfall and this, too, represents continuity – albeit of a regrettable kind.