In a slum on the outskirts of Kabul, a teacher tries to build a new country

by Jeffrey E. Stren

This month, the outgoing commander of America’s military effort in Afghanistantold Congress that the country the United States invaded more than 14 years ago was at “an inflection point.” The Taliban reportedly holds more territory than at any time since 2001, and civilian casualties are at record levels. Ethnic minorities are especially vulnerable; some fear that peace talks with the Taliban could open a place in the government for an organization that waged a campaignof ethnic cleansing against them.

For all of these reasons, even as U.S. forces continue to depart the country, the war in Afghanistan isn’t over yet, and by many measures it’s not going well.

But there are stories of hope, if you know where to look. One of the brightest is so small it’s invisible to many; to find it, you have to drive for the better part of an hour along rutted roads from the center of Kabul, to a Hazara slum in a desert on the city’s outskirts. It’s just a school. But it is, in many ways, exactly what the Americans and their Afghan allies have been fighting for more than a decade to protect. And it’s exactly what Afghanistan stands to lose now.

* * *

So it’s unsurprising that among those waiting for the Americans were some Hazara refugee kids huddled under a few UNHCR tarps in Pakistan, learning to read. The young man instructing them was Aziz Royesh, whom they referred to, simply, as the Teacher. The group could barely be called a school, but Aziz had given it a name that spoke to his hopes for it, a single Farsi word that meant many things: enlightenment, spiritual awareness, the kind of understanding that comes from experience. Marefat. The three syllables held what a person could provide herself, regardless of where she was, or what had happened to her parents during the civil war.

Then it was not just a school; it was a forward operating base from which Aziz nudged his community toward his own progressive way of thinking. He met with his students’ parents, who were often illiterate, so they could gain from their children’s schooling. The kids published bulletins with news from the school; they put out a magazine with poetry and editorials; and Aziz helped them organize political demonstrations. When then-interim President Hamid Karzai made his first visit to the desert after the fall of the Taliban, Marefat students lined up on either side of the street, waving Afghan flags and photos of him. And when the country had its first post-Taliban elections, the students organized on the challenger’s behalf, establishing the school as not just an educational and cultural force, but a political one as well.

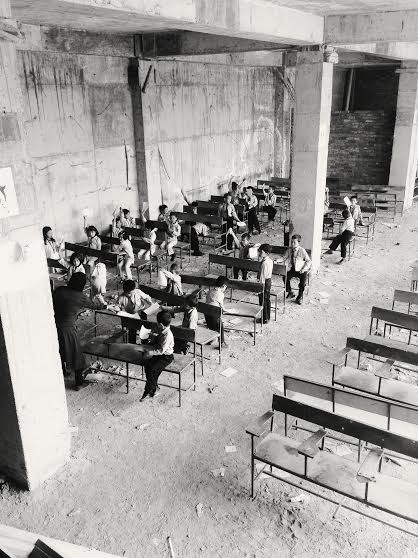

The contrast between what the school looked like—barren concrete walls and floors—and the energy in the classrooms was striking. I’ve seen students there debate whether racism in Afghanistan is worse than in countries they will never see, but whose histories they seem to understand as if they’ve lived it. I saw a girl say in class: “Racism is worse here because other countries made it worse,” speaking of the long history of foreign powers picking favorites among the ethnic groups in Afghanistan—Turkey supporting Uzbeks, Pakistan supporting Pashtuns, other groups with their other regional backers.

Yet for now, people like Aziz are trying to hold up their end of the bargain. The Americans, who may or may not be considering another five years of small-scale counterterrorism operations in the country, aren’t offering enough to hold up theirs.

Source: theatlantic.com