Identifying the Patterns of Oppression Toward Social Justice and Self-Determination

A draft application for a fictional citizen science project

Abstract

Using intersectionality as a theoretical ground, this paper drafts a fictional citizen science project to critically examine Hazara’s human rights situation toward social justice and self-determination. The Hazara are one of the most persecuted nations; besides facing systematic crimes, including genocide, slavery, discrimination, and forced displacement, they witnessed the invasion of their land Hazaristan. “From American Black Movements to Yellow Uprising of the Hazara in Hazaristan,” as a digital humanities project, tries to map the patterns of oppression by drawing the domination matrix. The project interacts with the Hazara to record their events, digitalizes the historical records and the Hazara folklore, and extracts data from other sources for a critical data mining process. It will reveal the active factors, and subfactors that intersect and the oppression agents use them to increase oppression. Those factors can be race and ethnicity, religion, geographical location, history, culture, language, and gender. In a dynamic approach, the project may discover some other invisible factors or are origins of other factors contributing to more marginalized margins connected to socially constructed privileges by oppression agents to make the victims more scattered and weaker to resist. The project may have short- and long-term effects impacting the balance of power in its setting.

Purpose and Aims

Can internationality travel from black feminism and black social justice movements to Hazaristan and perform as a framework identifying the patterns of the long-term oppression against the Hazara? Having a “work-in-progress understanding of intersectionality” and taking its dimensions, including its dynamics to travel internationally and “engage an ever-widening range of experiences and structures of power” (Carbado, Crenshaw, Mays, & Tomlinson, 2013), the project “From American Black Movements to Yellow Uprising of the Hazara in Hazaristan” employs intersectionality toward social justice and self-determination as a human right.

The project consists of an information system architected to interact securely with the Hazara and record events related to systematic crimes against them and any event related to their history and culture. Considering the critical aspects of text mining (Dobson, 2019a, 2019b), a part of the system is to digitalize the historical records and folklore. It also extracts data from online sources, including Papers Past Data from the National Library of New Zealand and the British National Archives for text and data mining. The system also has detailed guidelines for the users. It covers the related experiences in other parts of the world, particularly the black social and feminist movements. The data dynamically and manually tagged and mapped through drawing a matrix of domination containing privilege and oppression constructs for future analysis. The aim is to identify the original, invisible, and active factors of oppression and privilege and how they intersect/ed from the lens of intersectionality as a theoretical ground. It makes it possible to identify the pattern/s of oppression and how the past and current resistance approaches were/are shaped, and what approaches should be taken.

Why the Hazara and Hazaristan?

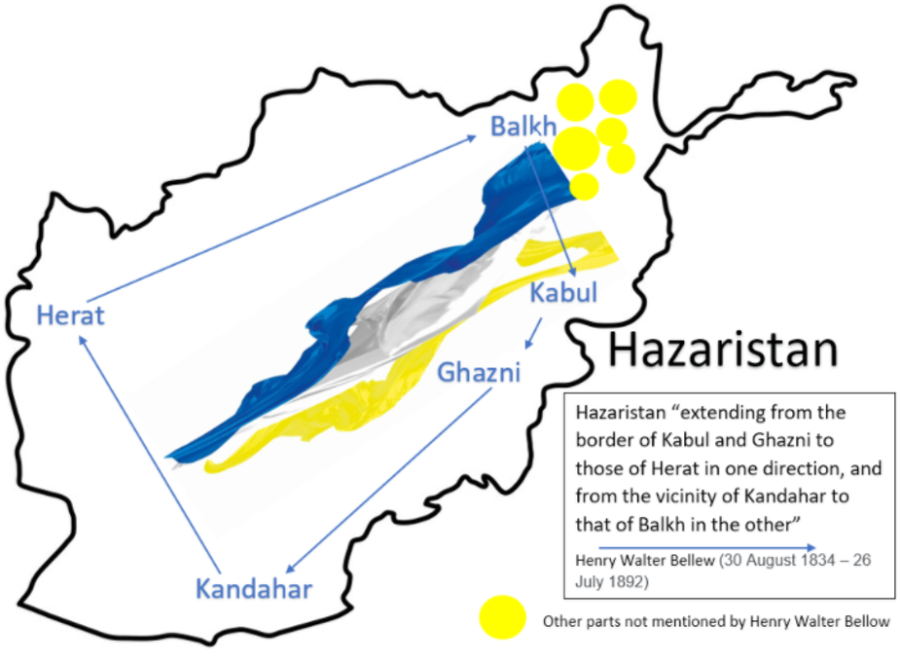

Starting from the 19th century, the Hazara of Hazaristan face continuous, systematic crimes, including genocide, slavery, ethnic cleansing, and forced displacement. They were once the largest ethnic group in their country. Their territory, Hazaristan, was expanded from the very south to the north and from the east to the west (Bellew, 1880, pp. 113-117; Minority Rights, 2015). While the systematic crimes against the Hazara continued in the 19th century, and tens of thousands of Pashtun tribesmen (Thames Star, 1892; Waikato Times, 1892) backed and armed by the British colonial officers were attacking and invading the Hazara Dai-s from Kandahar in the south of Hazaristan (Poets World-wide, 2017; Temirkhanov, 1980, pp. 259-260), the name Afghanistan appeared on the maps (Vivien de St Martin, 1825). In the last decade of the 19th century, over fifty percent of the Hazara population, including almost all Hazara leaders and their families, massacred (Poets World-wide, 2017, p. 257; Temirkhanov, 1980). In October 1893, many newspapers, including Hawke’s Bay Herald (1893), also reported that thousands of Hazara captives were sold as slaves. Katib Haz?rah (2016, p. 969) and Temirkhanov (1980, pp. 265-266) write that after the great genocide of the Hazara, the Hazara lands distributed among the Pashtun tribes. The remaining victims were forced to work on their own lands as invaders’ laborers and pay high taxes. If they could not, the alternative was their women and children as slaves.

As the Poets World-wide (2017) state in their open letter, the “entire 20th-century history has been marked by killings of Hazaras and systematic discrimination against them”. The Hazara were considered the lowest social class. They did not have the right and privilege to have a better social location than a Juwali, labor to carry heavy things, and ethnic teasing such as Hazara mouse-eater became normal. In the last decade of the 20th century, during the Pashtun Taliban’s ethnocratic and clerical regime, the policy was to force other ethnic groups to neighboring countries and the Hazara to the graveyard (Zabriskie, 2008). The outcome was the massacre of thousands of the Hazara and destroying their historical Buddhas in Bamyan, Hazaristan (Human Rights Watch, 1998; Poets World-wide, 2017). The systematic crimes against the Hazara did not end with the fall of the Taliban regime. Many well-educated Pashtuns enjoying the ethnic privilege and onboarded George W. Bush’s plane were appointed president, ministers, governors, and ambassadors to bring democracy (Santos & Teixeira, 2013). They later onboarded Trump’s plane to bring peace (Analytica). However, as it happened, in addition to converting the country into the most corrupted (Bak, 2019) and the biggest producer of opium in the world (Kamminga, 2019), systematic discrimination and organized bloody attacks on the Hazara increased. For instance, in July 2016, the Hazara Enlightenment Movement’s peaceful protest targeted by the Taliban-Daesh, after the regime forcefully isolates the rally in one part of Kabul, which in addition to the massacre, as the president of PEN International, Jennifer Clement, explains, it should be considered also censorship (Mir Hazar, 2020). As such, there are many other examples revealing the systematic crimes against the Hazara as well as destroying and falsifying of their history and culture.

State of the Art

There are dozens of studies that directly or indirectly investigated the human rights situation of the Hazara. However, a few studies used intersectionality as a theoretical ground for their investigations. A search within popular academic databases such as Business Source Elite, Academic Search Premier, and JSTOR in English language using keywords Hazara, Hazaras, or Hazaristan, and intersectionality with Boolean search operators returns no result or relevant results. Search in Google Scholars returns some, including irrelevant studies.

Existed studies using intersectionality as the theoretical ground or close to it are mostly in broader contexts, highlighting the social location/s of the Hazara immigrants and Hazara women outside Hazaristan or the so-called country Afghanistan. For instance, Botfield, Newman, and Zwi (2018) focused on young refugees, including the Hazara in Australia, and their sexual health care, generation, and culture. Snowden (2018), in a case study for master thesis, investigated the former Hazara unaccompanied asylum-seeking children who still are/were without documents in Malmö city of Sweden. They “raised in Iran as a marginalized minority,” and the Swedish authorities did not grant them asylum. The research is based on semi-structured interviews and observations, where the researcher used “institutional and societal impacts on an individual sense of belonging,” including emotional and political belonging justified and defined by Yuval-Davis, Anthias, and Kofman (2005). The researcher reported the interview results around “contact with family, impacts of institutional exclusions in Sweden, impacts on health, benefits of institutional inclusions, reliance on others, personal safety and othering, freedom of religion in Sweden and imagining the future. While Afghan as an identity for non-Pashtuns is in question (Lewis, 2011; Raofi, 2018), Alizada (2019) used intersectionality as a framework in her master thesis and focused on unaccompanied Afghan migrants in Sweden where all respondents happened to be Hazara. The study results show the struggle of those migrants to change the media image and their generalizations from the media. As such, studies focusing on the Hazara in the migration context are several.

Using the lens of intersectionality, Ali (2016) concentrated on the “faith-based violence in Pakistan” against female victims, including Hazara Shia, non-Hazara Shia, Sunni Barelvi, and Ahmadi. As the author emphasizes, the Hazara women’s ethnicity, religion, and gender intersect and make them easier targets for Deobandi extremists such as the Taliban, LeJ, SSP, and their affiliates. The author’s findings are on social, emotional, psychological, and economic impacts.

While searching, I came across an unpublished project by Potharaju (2018) titled “Intersectionality of Dual Identities: Afghani Hazara Women.” Only the project description is available, emphasizing that gender and ethnicity intersect and the “Hazara women are legally and socially denied of equal property rights.”

Intersectionality is new in the Hazara context, but it is coming to be more studies. However, most of the existed research projects ignore or unintentionally fall into a dominant narrative that a) Hazara are Shia, b) Hazara are Afghan, c) Hazara are descendants of Mongolian soldiers from the 13th century, d) and Hazara are a minority group. It is while a significant part of the Hazara is Sunni, Ismaili, Christian, or non-believer (Council of Sunni Hazara, 2016; Shariati, 2018; Yale MacMillan Center, 2018); still, after a long-term experiencing ethnocratic and ethno-clerical regimes, Afghan could not become an acceptable identity (Lewis, 2011; Raofi, 2018); historical evidence, including the Buddhas of Hazaristan in ancient Bamyan (Poets World-wide, 2017) confirm Hazara’s history, and so far, no genetic study with DNA samples confirms that Hazara are descendants of Mongolian soldiers (Das & Upadhyai, 2019; Gary, 2008; Li et al., 2008). There is also no reliable data and census about the population of the country. Such dominant narrative within literature supports the narrative of oppression against the Hazara, which impacts greatly in many aspects of their life.

The few existing studies investigated only three social locations, including ethnicity, gender, and religion, which are not enough to map the margins (Crenshaw, 1990). There might also be other locations, such as geography, history, language, and culture, as active factors or invisible or origins generating or processing the current marginalization factors.

Societal Impact and Scientific Novelty

The project “From American Black Movements to Yellow Uprising of the Hazara in Hazaristan” is almost new in its context. Taking the work-in-progress understanding of intersectionality (Carbado et al., 2013), besides critical approaches of text and data mining (Dobson, 2019a, 2019b) and the engagement and interaction of the Hazara in recording the events related to their human rights situation as well as folklore, can be considered as a transform to digital humanities. A movement that takes “private marginalia to public, scholarly, dynamic interaction” (Mandell, 2019).

In the short term, the project might put a question mark in front of each Hazara. How many of them have lost their lives that even the public media do not cover in most cases? Am I the next target? It may generate other questions such as to what stand the oppression is internalized? Such questions may lead them to critical thinking of their situation and reemerge their selfhood.

On the other hand, the oppression agents may activate forcefully to stop the process or use techniques such as pretending that the agents in the privileged locations are victims of racism. As the oppression system is ideologically and institutionally organized and moves interpersonally around, the oppression agents may run propaganda. Discriminating arguments, such as “we are all Muslims, and we are all brothers, and we are all Afghans,” are common. Such actions may increase social tensions bringing political consequences as the project documents and mobilizing the knowledge (Safiya Umoja, 2019). However, the Hazara is in a critical position, facing genocide, standing between life and death. In the short term, the project may also encourage other indigenous peoples, such as the Uzbeks and Turkmens of South Turkestan, to co-operate and start their similar projects.

As the matrix of domination is forming, and the pattern/s of oppression are being identified, the Hazara may start thinking strategically, developing more strategic social movements. It would be easier for the Hazara to discover their social locations and attacks on Hazaristan culture and history in a broader picture. They can identify such crimes’ connections with events such as close ties of the ethnocratic Afghani regime with Nazism based on the Arian race (Farhang, 1988). Using the experience of other oppressed peoples and nations, we may witness an end to self-censorship and internalized oppression, a paradigm shift among the Hazara and their social movements toward social justice and the right of self-determination. In the long term, The Hazara may have established a good connection with other oppressed peoples and nations. We may also witness the rise of organized feminism in Hazaristan, influencing neighboring peoples and nations.

The project may also give the scholars a clear picture and new investigation areas on the Hazara’s past and contemporary situation without intervention of the dominant paradoxical narratives. The project may also make organizations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the United Nations Human Rights Council, and the International Criminal Court think about the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide and the genocide acts against the Hazara.

Source: Kabul Press

References

Ali, F. (2016). Experiences of Female Victims of Faith-Based Violence in Pakistan. In Faith-Based Violence and Deobandi Militancy in Pakistan (pp. 163-185): Springer.

Alizada, N. (2019). “Am I What You See?” Unaccompanied Afghans in the Swedish media and their integration prospects.

Analytica, O. US-Taliban deal a long way from securing Afghan peace. Emerald Expert Briefings(oxan-db).

Bak, M. (2019). Corruption in Afghanistan and the role of development assistance: JSTOR.

Bellew, H. W. (1880). Races of Afghanistan. London: Trubner and CO. W. Thacker and CO.

Botfield, J. R., Newman, C. E., & Zwi, A. B. (2018). Engaging migrant and refugee young people with sexual health care: Does generation matter more than culture? Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 15(4), 398-408.

Carbado, D. W., Crenshaw, K. W., Mays, V. M., & Tomlinson, B. (2013). Intersectionality: Mapping the movements of a theory. Du Bois review: social science research on race, 10(2), 303-312.

Council of Sunni Hazara (2016, 2016). ????? ?????? ????? ??? ??? ????????? [Facebook]. Retrieved

Crenshaw, K. (1990). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stan. L. Rev., 43, 1241.

Das, R., & Upadhyai, P. (2019). Investigating the West Eurasian ancestry of Pakistani Hazaras. J Genet, 98(2), 1-10. doi:10.1007/s12041-019-1093-2

Dobson, J. E. (2019a). Can an Algorithm Be Disturbed? In: University of Illinois Press.

Dobson, J. E. (2019b). Digital Historicism and the Historicity of Digital Texts. In: University of Illinois Press.

Farhang, M. S. (1988). ????????? ?? ??? ??? ????. Virginia: Ihsanullah Mayar.

Gary, S. (2008). Traces of a DISTANT PAST. Sci Am, 299(1), 56-63. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0708-56

Hawke’s Bay Herald. (1893). INDIA. Hawke’s Bay Herald, p. 2. Retrieved from https://paperspast.natlib.govt…

Human Rights Watch. (1998). Afghanistan: The Massacre in Mazar-I Sharif: Human Rights Watch.

Kamminga, J. (2019). States simply do not care: The failure of international securitisation of drug control in Afghanistan. International Journal of Drug Policy, 68, 3-8.

Katib Haz?rah, F. M. (2016). The History of Afghanistan: Fayz Muhammad Katib Hazarah’s Siraj Al-tawarikh (R. McChesney & M. M. Khorrami, Trans. Vol. 3): Brill.

Lewis, M. W. (Producer). (2011, 11.11.2020). The Complex and Contentious Issue of Afghan Identity. GeoCurrents. Retrieved from https://www.geocurrents.info/p…

Li, J. Z., Absher, D. M., Tang, H., Southwick, A. M., Casto, A. M., Ramachandran, S., . . . Myers, R. M. (2008). Worldwide Human Relationships Inferred from Genome-Wide Patterns of Variation. Science, 319(5866), 1100-1104. doi:10.1126/science.1153717

Mandell, L. (2019). Gender and Cultural Analytics: Finding or Making Stereotypes? In (pp. 3): University of Minnesota Press.

Minority Rights, G. I. (Producer). (2015, 06 19). Hazaras. Retrieved from https://minorityrights.org/min…

Mir Hazar, K. (2020). Sensur i Afghanistan. Unpublished, Bergen: Morgana Press.

Poets World-wide (Producer). (2017, 03 21). An Open Letter from the Poets World-wide to the Hazara, Civil and Human Rights Organizations, Immigration Authorities, and World Leaders. Hazara Rights. Retrieved from http://hazararights.com/spip.p…

Potharaju, J. (2018). Intersectionality of Dual Identities: Afghani Hazara Women. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/p…

Raofi, W. (2018). National Identity Crisis Threatens Afghanistan Peace. Retrieved from https://tolonews.com/opinion/n…

Safiya Umoja, N. (2019). Toward a Critical Black Digital Humanities. In (pp. 27): University of Minnesota Press.

Santos, M. H. d. C., & Teixeira, U. T. (2013). The essential role of democracy in the Bush Doctrine: the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan. Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, 56(2), 131-156.

Shariati, H. (2018). ????:? ????????? ??? ???» ?????????. Retrieved from ????:?«????????? ??? ???» ?????????

Snowden, S. (2018). Marginalised belonging: Unaccompanied, undocumented Hazara youth navigating political and emotional belonging in Sweden.

Temirkhanov, L. (1980). ????? ??? ????? (A. Toghyan, Trans.). Quetta: ????? ??? ?? ?????.

Thames Star. (1892). THE HAZARA REVOLT. Thames Star, p. 2. Retrieved from https://paperspast.natlib.govt…

Vivien de St Martin, L. (Cartographer). (1825). Carte Generale du Royaume de Perse et du Royaume de Caboul ou Afghanistan. Par L. Vivien, Geographe. Grave par Giraldon Bovinet. 1825. A Paris. Chez Menard et Desenne, Libraires Rue Git le Coeur, No. 8. [Atlas Map]. Retrieved from https://www.davidrumsey.com/lu…

Waikato Times. (1892). AFGHANISTAN. Waikato Times, p. 3. Retrieved from https://paperspast.natlib.govt…

Yale MacMillan Center. (2018). Conference discusses emerging identities in Afghanistan. Retrieved from https://iranianstudies.macmill…

Yuval-Davis, N., Anthias, F., & Kofman, E. (2005). Secure borders and safe haven and the gendered politics of belonging: Beyond social cohesion. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28(3), 513-535. doi:10.1080/0141987042000337867

Zabriskie, P. (2008). Hazaras: Afghanistan’s Outsiders. National Geographic.