By Jessica Donati

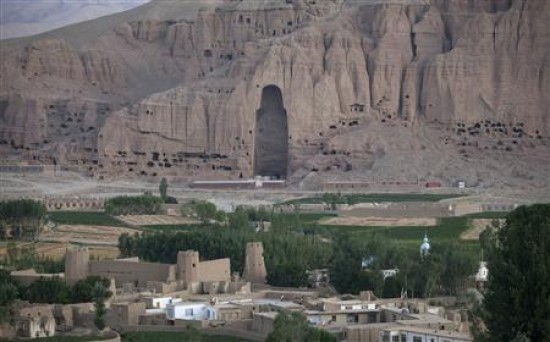

(Reuters) – Violence is returning to what has long been the most tranquil region of Afghanistan, where fears of a resurgent Taliban are as stark as the ragged holes left by the bombing of two ancient Buddha statues in cliffs facing the Bamiyan valley.

Bamiyan had been seen as the country’s safest province due to its remote location in the central mountains and the opposition of the dominant local tribe, the Hazara, to the Taliban, mostly ethnic Pashtuns who massacred thousands of Hazara during their austere rule.

But now, after 11 years of a NATO-led war against the Islamists, insurgents are edging back into the province, burying roadside bombs and striking at foreign and local security forces. Five New Zealand soldiers were killed in August.

The violence in a region that was a bellwether for NATO’s Afghanistan strategy underscores how rapidly security could deteriorate across the country once foreign combat soldiers leave by the end of 2014.

Local people say the insurgent stranglehold is now so tight that the province is effectively cut off by road in all directions and safely reachable only by air.

“When there are no flights out of Bamiyan, I put myself in the hands of God and travel by car,” says District Governor Azim Farid, now sheltering in the capital Kabul.

Adding to the despondency is a decision earlier this year by UNESCO, the United Nations cultural agency, to call off negotiations to rebuild the two ancient Buddha statues, destroyed by the Taliban over two weeks in 2001 because they offended religious fundamentalists. UNESCO cited funding constraints.

NATO-led coalition forces say the recent insurgent attacks in Bamiyan are a tiny fraction of overall attacks across Afghanistan, although it could represent an attempt by the Taliban to retake the initiative.

“There has been an increase, but to put it in perspective this accounts for 0.06 percent of the total enemy-initiated attacks in all of Afghanistan,” a coalition spokeswoman said.

Until the attacks began to spiral in July, when nine Afghan police were killed in two bombings, Bamiyan was a NATO success story.

It was one of the first provinces where security was handed over to Afghan forces in 2011, raising hopes that even tourists could soon be revisiting Bamiyan’s soaring mountains, plunging azure lakes and ruined forts that once held out against an attack by a son of the Mongol emperor Genghis Khan.

Last winter, the province hosted a small international ski competition.

Now, local residents are trying to arm themselves, as they did during the brutal civil war between rival ethnic warlords that left thousands dead in the 1990s.

“The people are thinking the best course of action is to re-arm in any way possible to prepare for the Taliban coming back and preventing another slaughter,” says Farid, his face etched with worry as he looks into an untouched mug of saffron tea.

“People regret handing weapons to the government in the past and accepting that the government would bring the rule of law because the government so far has been unable to protect them.”

JEWS OF AFGHANISTAN

While eyeing new guns, the Hazara, among the poorest people in the country, are arming themselves with whatever is at hand, from axes to farming scythes and any old weapons left behind.

Most Hazara are Shi’ite Muslims and they are sometimes called the ‘Jews of Afghanistan’ because of their slaughter and persecution by the Taliban, who are strict Sunni Muslims and consider the Hazara as infidels.

“We are surrounded by different ethnicities, on this side and this side,” says local spice shop owner Aziz, who only has one name, gesturing at the Hindu Kush ranges ringing his village which become blanketed in heavy snow during the bleak Bamiyan winters.

To the south and east are the Pashtuns, where the Taliban draw most of their support. To the north are the Tajiks and the Uzbeks, who are no friends of the Hazara either.

When NATO transferred the province to Afghan security control, the government promised to send more police, intelligence officers and an army unit.

But with the 350,000 strong Afghan security forces stretched to combat the insurgency in the Taliban’s southern and eastern strongholds, those reinforcements never arrived and police numbers have been cut by a fifth from around 1,000.

That has led to the Taliban spilling into Bamiyan from neighboring provinces. Government supporters have been dragged out of their cars at makeshift roadblocks, one was beheaded for simply for wearing a Western t-shirt.

Residents say that when tied to the threat of roadside bombs, they are effectively trapped in the safer central parts of the province.

“So many wars have passed through here and I have experienced them all. No one wants to protect us and look after security here,” says Aziz, 44, sitting cross-legged in his shop.

Deteriorating security is also threatening to derail the biggest foreign investment in Afghanistan’s resources sector, an $11 billion project to extract iron ore from the Hajigak mines in Bamiyan.

“The private company has expressed serious concern about security at Hajigak, so the government is coming up with a strategy,” said senior engineer Abdul Hakim Hikmat at his office at Bamiyan’s Ministry of Mines.

ETHNIC SLAUGHTER

When the Taliban last ruled Bamiyan, they took Aziz’s shop and belongings, killing one relative. If they return again, the only option is to fight or flee, because foreign military protectors will have left the country, he says.

“We’ll cross the Babbar Mountains to a district where there are other Hazara,” he said. Up to half a million Hazara, easily identified because of their Asiatic features, have already fled to neighboring Pakistan and onward to seek asylum in Western countries from Europe to Canada and Australia.

The Taliban now effectively control the north and eastern Bamiyan districts of Kohmard and Shibar, according to the United Nations, because outgunned police stopped patrolling those areas about six weeks ago in the face of the Taliban threat.

Bamiyan’s Governor Habiba Sarabi, the only woman to run one of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces, says reinforcements are on their way from the central government, although she could not say when.

“This is their duty. They have to do something,” she said.

The central government had pinned hopes for tourism on development in Bamiyan, which used to draw thousands of tourists each year to see the ancient Buddhas and the lakes of Band-e-Amir, grouped into Afghanistan’s first national park in 2009.

While the lakes remain free from insurgent activity, the Taliban’s grip on roads into the province has choked off tourist flows.

Colored swan paddle boats are unused even on the Friday holiday, with just a handful of locals strolling beneath the dramatic cliffs with their families.

“The real tourists are not here because of problems with the highways in Bamiyan,” says Sayeed Ismaeel Balaghi, who owns the boats and who has lived by the lakes for half a century.

On the streets of the main provincial town, also called Bamiyan, many people are fatalistic.

“Of course the Taliban will come here and fight against the people,” says 23-year-old Fato, selling fruit from a wagon. “Maybe the people can defend themselves, maybe not.”

(Additional reporting by Hamid Shalizi and Mirwais Harooni; Editing by Rob Taylor and Raju Gopalakrishnan)