Posted by Saleem Ali of University of Vermont (USA)

By Saleem H. Ali and M. Saleem Javed

The current predicament of ethnic and religious minorities in Afghanistan and Pakistan is a cause of grave concern, and it is essential for the international community to be aware of multiple complexities and rivalries in the region. For this article I partnered with an ethnic Hazara human rights activist and Chinese-educated medical doctor, M. Saleem Javed, based in Quetta, Pakistan to provide a brief history of this threatened community and to document the challenges they are currently facing.

Origin and Identity

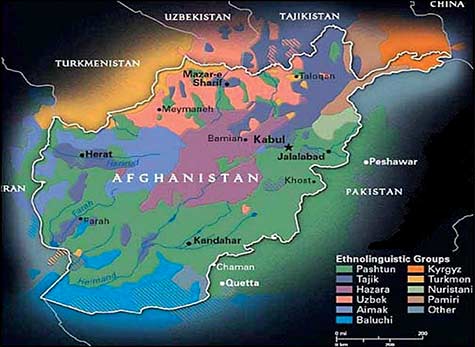

Central Asia has been the crossroads of ethnicities for millennia as exemplified by the diversity of languages and other cultural expressions in this region. The West has been exposed to these narratives in the past decade unfortunately through the lens of conflict in Afghanistan. As NATO forces withdraw from the region, the plight of indigenous minorities deserves greater attention and scrutiny. Perhaps the most vulnerable of these minority groups are the Hazara people. Phenotypically, the Hazara have distinct similarities to Mongols and there may have been an ethnic connection as evident from the etymology of many Hazara names. There was likely widespread intermarriage when the Mongols invaded South-central Asia in the twelfth and the preexisting descendants of the Indo-Hephthalite Kushan Buddhist empire as well as subsequent Persian settlers.

A Chinese traveler, Tauchaun, wrote about people similar to Chinese in Hazarajat called ‘Hosalo’ in June 644 A.D. Since the Chinese alphabet does not have an ‘R,’ this reference could have been ‘Hozora’ or Hazara’. The proximate etymology of the word is derived from the Persian word for a ‘thousand’ (Hazar) which may be a reference to a military contingent. During the various conquests of the times perhaps this syncretic identity emerged beyond the battlefields. Now more than 5 million people consider themselves to be Hazara, a vast majority of whom live in Afghanistan (constituting at least 20% of the country’s population), followed by around a million in Pakistan. In Iran, there is a sizeable population of Hazara but they are intermingled with the Khawari ethnic group and a definitive census is hard to determine. The largest Hazara diaspora abroad is in Australia, which has been welcoming of Afghan immigration due to old ties of Afghan workers during British colonial times (even now one of Australia’s major train lines is called “The Ghan” in respect of this legacy).

Marginalization and Conquest

Discrimination towards the Hazara was poignantly portrayed by Afghan-American writer Khaled Hosseini in his epic novel The Kite Runner. The roots of persecution towards the Hazara are largely related to sectarian rifts within Islam – the dominant religion in the region. Though a comprehensive census eludes us, it is fair to say that a vast majority of Hazara are Shia (believing in twelve imams) with small Sunni and Ismaili minorities as well. While a majority of Pashtuns are Sunnis, there are also several Shia groups within Pashtun ranks, particularly among the Orakzai tribes. As documented in Sana Haroon’s book Frontier of Faith, there were several episodes of anti-Shia movements during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Most notable among these was the one led by Mullah Mahmud Akhunzada against the Shias of Orakzai which led to a bloody confrontation and expulsion of many Shias in 1929. The British supported the Shia at the time as a persecuted minority, though tribal leaders (particularly the Afridis) were highly suspicious of British intentions and tried to prevent their intervention by mobilizing their own dispute resolution system with the mullahs.

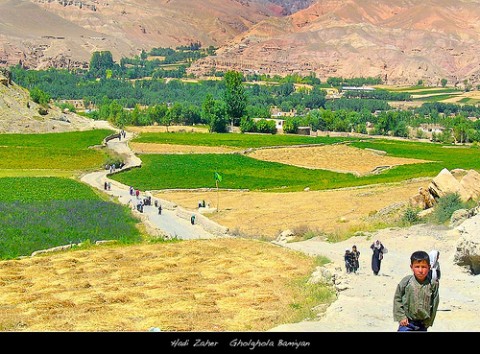

The inhabitants of Hazarajat in the central highlands of Afghanistan, were semi-independent until Amir Abdul Rahman, the King of Afghanistan, invaded their homeland in the late nineteenth century with the help of Sunni clergymen who declared Jihad (religious decree) against the Hazara Shias. According Afghan historian Mir Ghulam Mohammad Ghubar The Amir’s army and tribal militiamen massacred almost 60% of the Hazaras, confiscated much of their fertile land and enslaved many others. Many of them sought refuge in Quetta Pakistan and Iran’s Mashhed at that time leading to current populations in these areas. The remaining population has faced persecution and social discrimination at the hands of Afghan rulers ever since then.

Similar dynamics of dissent and conflict with foreign forces in the region appear to be playing out almost a century later. In March 1979 the Hazara launched a major offensive against the communist Afghan government and claimed their homeland (Hazarajat) in just a few months. However, in the 1980 various Hazara factions were engaged in a civil war while trying to establish domination over Hazarajat which ended in 1988 under the platform of the Hizb-e-Wahdat.

Taliban terror and its aftermath

Following the Russo-Afghan war and the subsequent Afghan civil war, the Taliban toke over Kabul in 1996 which marked the beginning of another wave of persecution and repression against the Hazara. From 1998 to 2002 thousands of Hazaras were massacred by Taliban in Mazar-e-Sharif (1998) , Rotak Pass (2000), Bamiyan (1998 -1999) , Yakao lang (January 2001) and other places of Afghanistan. Human Rights Watch (HRW) has documented through archived sources the massacre of thousands of Hazara Shias by Taliban forces during these years. Mullah Manan Niazi, the Taliban governor of Mazar-e-Sharif, had issued a Fatwa that ‘Hazaras are not Muslim, killing them is not a sin’. While the Taliban did make some tentative alliances with a few Hazara, it is widely believed that it was an official policy of the Taliban to marginalize the Hazara, confiscate their lands and force them into exile, particularly in Iran.

Termination of the Taliban government was wholeheartedly welcomed by the Hazaras and other ethnic and religious minorities in Afghanistan. The situation greatly improved as compared to Taliban times as the Afghan constitution gave fundamental protection to persecuted minorities, including the Hazara. However, minority communities continued to have grievances even under Hamid Karzai’s democratic government and violence continued. In 2004, 16 Hazaras were pulled from their vehicle by Taliban forces in south-central Afghanistan and executed. Hundreds of them have been massacred by Kochi nomads—who are presumptively allied with Taliban — in Behsud since 2007. Afghanistan’s Independent Human Rights Commission has produced a report on the dreadful series of incidents in this region.

Quo vadis NATO?

After ten years of the presence of US led NATO forces and at the eve of their withdrawal, there are ominous signs of a return to wider persecution of the Hazara Shias. On December 7, 2011 more than 70 Shias, mostly Hazaras, were killed in simultaneous suicide attacks on the tenth day of Moharram in Kabul and Mazar e Sharif. These attacks were ambiguously claimed and then denied by Lashkar-e-Jhangvi-al-Alami, a Pakistan based Taliban affiliate, with historic ties to Pakistani intelligence services that have operated under the despicable doctrine of “strategic depth” (exerting influence through destabilization of Afghanistan in order to gain leverage with their arch-rival India).

Similar attacks have taken place against the Hazara Shias of Pakistan since 1999 in which more than 700 innocent people have lost their lives along with hundreds injured and maimed. Two of the worst attacks which shocked the world were when 29 Hazara passengers were taken off a bus, made to stand in line and executed one by one in Mastung on 20 September 2011. Another 13 were executed after being identified as Hazaras Shias in Akhtarabad, Quetta, on Oct 04, 2011. The responsibility of almost all such attacks/targeted killings have been claimed by Lashkar e Jhangvi. A few weeks before the massacre, this banned terrorist outfit had circulated an open letter addressed to Hazaras in Quetta reading: “All Shi’ites are worthy of killing. We will rid Pakistan of unclean people….”

London-based Minority Rights Group (MRG) has identified the Hazara as the ‘most under threat minorty group’ in Afghanistan. The Hazara, both in Afghanistan and Pakistan, have been persecuted because of their religious and/or ethnic heritage and are particularly fearful of the peace talks with Taliban that are being brokered by Qatar. These talks may lead to the release of a particularly ruthless anti-Hazara Taliban commander and former deputy defense minister in their regime, Mullah Muhammad Fazl from Guantanamo Bay, who is known for his pernicious attacks on Shias.

For peace to prevail in Afghanistan and Pakistan, assuring security of the Hazara minority is essential. The United States and all interested states must not compromise on the security of this persecuted minority population in their peace talks. The Hazara constitute a vital indigenous culture that has survived for centuries and is threatened. While all groups must try to promote sectarian harmony internally, the responsibility of protecting the fundamental human rights of the Hazara remains with the Afghan and Pakistani states and their allies who purport to support peaceful pluralism.

FromToronto

since when are Hazaras a minority? Why do we keep calling ourself minority. This is what happens when others identify us and our own young just follow them.