Dilipkumar, 2 Jan 2011

It’s almost a decade the World’s tallest standing Buddha’s statues of Bamiyan were obliterated…An incident which can’t be justified on any account . It’s inherent human nature to create and destory…

Ancient archaeological remains have been thrust into the cruel world of today’s seemingly endless conflicts — the ever-changing aims and alliances of international politics, religions dueling on the world stage, and the ironic trade-off of providing aid to conserve the material heritage of the past but not to preserve the lives of modern inheritors of that past. Arrayed against the tolerant and measured messages of Buddhism, the quagmire of the “Bamiyan Massacre” was perplexing at best.

In the center of Afghanistan, the town of Bamiyan, situated ca. 200 km NW of Kabul at an altitude of approximately 2500 meters, is considered an oasis in the center of a long valley that separates the big chains of Hindu Kush Mountains. Bamiyan functioned as one of the greatest Buddhist centers for nearly five centuries. It’s a place of open fields and sky, with a long, rich history – evidences of which were destroyed even before scholars could start understanding it fully.

The valley, at an altitude of 2,500 m, follows the Bamiyan River. Some 1,500 years ago, the valley was a busy node on the trade route between China and India, in a part of Asia where languages and religions — Buddhism, Hinduism and, later, Islam – coexisted. It was inhabited and partly urbanized from the 3rd century BC.

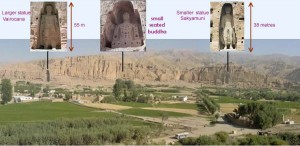

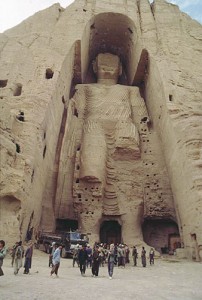

It was also home to a great Buddhist monastic center, one that nurtured epoch-changing religious concepts and produced a fantastic new art, including the world’s largest rock-carved figures of the standing Buddha. Among the tallest standing Buddhas in the world, the Bamiyan, Afghanistan Buddhas stood 53 meters (175 feet) and 34.5 meters tall. These two big standing Buddha statues and a small of a seated Buddha were carved out of the sedimentary rock of the region. They were begun in the second century A.D. under the patronage of Emperor Kanishka and probably finished around the fourth and fifth centuries A.D.

The smaller statue (lower image) was ca. 38 metres (115 feet) high and it was situated at the eastern end of the cliff. It was painted in blue and probably represents Buddha Sakyamuni. The two colossi must once have been a truly awesome sight, visible for miles, with copper masks for faces and copper-covered hands

The two large Buddhas were cut in deep relief directly from the rock. The surrounding cliffs were honeycombed with dozens of small caves, dug out either as monastic residences or for rituals. Many caves, along with the niches around the Buddhas, were covered with murals, now largely damaged or missing.

In 16th century CE, the site is reported to have contained some 12,000 caves, forming a large ensemble of Buddhist monasteries, chapels and sanctuaries, along the foothills of the valley. A preliminary geophysical exploration in 2002 has indicated the presence of ancient roads and wall structures. In several of the caves and niches, often linked with communicating galleries, there are remains of wall paintings. There are also remains of seated Buddha figures.

The art is a compendium of ancient styles, from India, Persia and Gandhara, where Greco-Roman-inspired traditions survived. Along with its stylistic dynamism, Bamiyan statues reflect major shifts in Buddhism itself. For centuries, the Buddha was revered as a human figure, but with time he came to be seen as a transcendent being and icon. These towering, transcendental images were key symbols in the rise of Mahayana Buddhist teachings, which emphasized the ability of everyone, not just monks, to achieve enlightenment.

For centuries they gazed benevolently from their mountain homes as wars raged across the Afghan plains in central Bamiyan province. Hewn into the cliffs in the sixth century by Buddhist pilgrims on the famed Silk Route, the statues had survived attacks by several Muslim emperors down the ages, while even Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan had spared them. Based on present practices using only hand labor and simple tools, the statues could have been craved in a few decades. But the two massive Buddha statues have become casualties, destroyed by command of the Afghan Taliban in early March 2001 in a week time.

In 1998, a Taliban commander fired grenades at the smaller statue, knocking off its upper half. The Taliban bombed the mountain above the statues frequently, cracking the niches that held the statues and damaging the colossi further. By winter 2001, pleas were raining down on the Taliban from around the world to spare the statues. Pleaders included the Buddhist Thai monarchy and Sri Lanka, itself home to a set of giant Buddha statues. “Unesco, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and a leading Islamic scholar in Cairo were also among those begging the Taliban not to carry out their threat to the Bamiyan statues and other Buddha images in museums across the country,” wrote Barbara Crossette in The New York Times.

But, to no avail.

On Feb. 26, 2001, the Taliban’s supreme leader, Mullah Mohammad Omar with the backing of Osama bin Laden’s Al-Qaeda movement, declared that “these idols have been gods of the infidels” and ordered them destroyed. Defying international appeals, the Taliban spent a month using first anti-aircraft guns and then dynamite to obliterate them. By early March, the statues were rubble.

That sight is now retrievable only when pieced together from material evidence. And evidence, at Bamiyan and elsewhere in Afghanistan, may be going fast. The fate of thousands of precious objects in the Kabul Museum, one of the most important collections in Asia, is unknown. Among its treasures are the priceless Begram ivories, pocket-size carvings that in art-history terms have a weight as ponderous as the Bamiyan colossi.

Today those open, cold caves are used primarily by refugees from Afghanistan’s brutal, internal war.

The world community — from Russia to Malaysia, Germany to Sri Lanka, and, of course, UNESCO — has expressed horror at the Buddhas’ destruction. Many Mullahs in Islamic countries condemned Mullah Omar’s interpretation as wrong-headed and damaging to the image of Islam.

It is fitting that in his previous lives, as recorded in Jakata Tales, the Buddha often sacrificed himself, becoming food for a tiger and her cubs, for instance, and for a hungry hawk chasing a pigeon. But while the Buddha had learned to accept impermanence, we mortals couldn’t ……

The New Findings

It is believed that they are the oldest known surviving examples of oil painting, possibly predating oil painting in Europe by as much as six centuries.

On 8 September 2008 archeologists searching for a legendary 300-metre statue at the site of the already dynamited Buddhas announced the discovery of an unknown 19-metre (62-foot) reclining Buddha, a pose representing Buddha’s passage into nirvana.

A Video by UNESCO

Source: http://dilipkumar.in